International Youth Water Justice Summit

Join the U.K. Appalachian Center for the International Youth Water Justice Summit at Memorial Hall on Saturday, July 12th, 2014 from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. This event is free and open to the public; all ages are welcome to attend (children under the age of 16 must be accompanied by a parent or guardian). Lunch will be provided. There will be presentations and activities related to water justice locally, regionally, and globally throughout the day. Water justice refers to fair and inclusive distribution and stewardship of water resources. This is an opportunity to think about how you are connected to everyone in the world through water, from the make-up of the human body to the watersheds providing us with drinking water to the river, ocean, and weather systems that keep water circulating.

Here is the schedule for Saturday's events:

Just outside Memorial Hall (or in the lobby, if raining) will be these hands-on activities through the day:

9-5 Enviroscape (Bluegrass GreenSource)

11-2 Paint your watershed (KY Riverkeeper)

9-5 Meet a salamander (UK Forestry/Appalachian Center)

Inside Memorial Hall:

9:00-9:15 Welcome

9:15-10:00 Introduction to the Kentucky River Watershed by the KY Riverkeeper

10:00-11:00 Global discussion of water issues between those in Memorial Hall and young people joining us electronically from Morocco and Turkey

11:00AM-12:00PM Examples of community forestry/water management from Indonesia

12:00-1:00 Outside (weather permitting): lunch; inside: screening of the film THIRST

1:00-1:30 Panel/discussion: participants in the International Youth Water Justice Workshop in the Robinson Forest in Appalachian Kentucky, 7/7-11/14

1:30-2:00 Presentation/discussion: the state of global rivers

2:00-2:15 Break

2:15-2:45 Presentation/discussion: water crises close to home that have and have not made the news, and responses to them

2:45-3:00PM Movement/music

3:00-4:30 Kentucky examples of community-based watershed decision-making and monitoring: Kentucky Water Resources Research Institute

4:30-5:00 Closing discussion

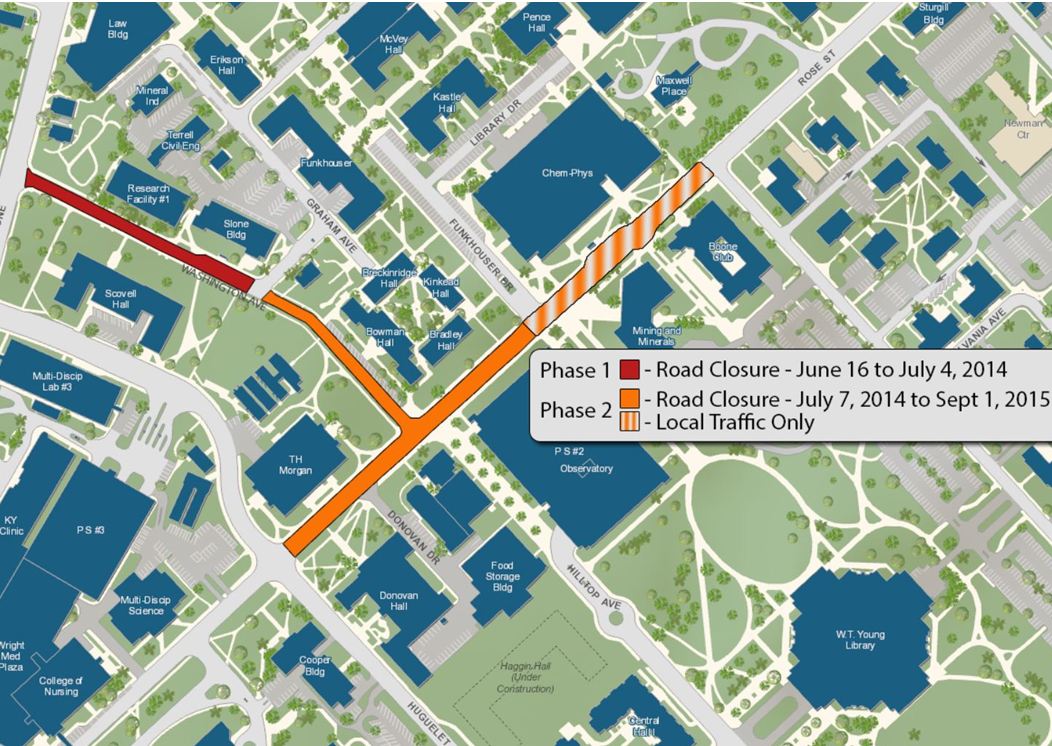

A map for reference can be found here: http://www.uky.edu/pts/sites/www.uky.edu.pts/files/pdfs/ukpts-parking-map-summer-large.pdf. Parking closest to the event site of Memorial Hall includes the Rose Street Parking Structure #2 (located off of University Drive, with access from Hilltop Avenue), lots located off of Rose Street on Funkhouser Drive, and lots located between the Slone Building and the back of the Funkhouser Building off of Washington Avenue (via Gladstone). Please, see the construction plan map below and note that it is subject to change. It may be necessary to park in one of the alternate locations listed above.

For more information please contact Erin Norton, Department Manager at the UK Appalachian Center, 859-257-4852, erin.norton@uky.edu. To learn more in general about the UK Appalachian Center, you can visit our website at appalachiancenter.as.uky.edu/