By Francis Von Mann

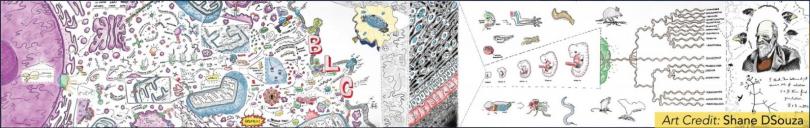

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Oct. 8, 2025) – In the Jacobs Science Building, a mural sprawls across a whiteboard. On one side, a magnified cell with swirling, intricate layers. On the other, Charles Darwin circled by Galápagos finches and double helixes. It is equal parts science and art, memorialized with a signature in the corner: Shane D’Souza, Class of 2018.

Seven years later, D’Souza stands in front of that same mural – untouched by students who have long admired it – delivering a lecture on his research in pediatric ophthalmology. The audience of biology undergraduates leans in. His subject is technical, but his metaphors are clear and vivid. What captivates students is not only science, but how D’Souza frames it.

“Oftentimes the way I proceed with talks is not about giving the talk to scientists, but as sort of an educator,” he explained. “I’m trying to teach everyone in the room what I’ve been working on for a while.”

Dr. Shane D’Souza is now an research fellow in the Department of Pediatric Ophthalmology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. But his start in research came at the UK College of Arts and Sciences as a biology student.

“I caught the research bug early because I had such phenomenal mentors, and I think I have been stuck in this rabbit hole and been digging deeper and deeper since then, all because of just how incredible they were at teaching and instilling the importance of discovery,” D’Souza said.

The idea that he could “be exploring the unknown” hooked him, even though he recalled “I don’t think I ever was able to be like, ‘I did a successful experiment’ and I put the lab notebook down.”

Still, he kept going. What fueled him was curiosity and the belief that the classroom knowledge he was gaining could be applied to real problems.

If research was one spark, teaching was another. As friends began asking him to explain concepts in organic chemistry, he realized he had a gift. In 2016, he joined the new Organic Excel program and soon after became a tutor in the Biology Learning Center.

“It was the fill to my cup that research kind of was draining,” he said. “Helping somebody have their eureka moment… just brought me a lot of joy at the end of the day.”

On Friday nights, he packed lecture halls with students eager to work through worksheets he designed.

“We would have a whole lecture hall where all of these guys are doing stupid worksheets that I made,” he remembered. “It was just this idea of being able to help people learn what they could have done had they had the formulated input that they needed to be successful.”

Today, his research explores how the eye and brain connect during early development. The work has implications for premature infants in neonatal intensive care units, where lighting conditions vary dramatically.

“There really isn’t a standard of care for the lighting environment in a neonatal intensive care unit for sick children,” D’Souza explained. “That means everyone is doing their own thing.”

The stakes are high. “We know now that having lighting in the environment is a critical component of your development for many, many different organisms to develop normally,” he said. “But the concern becomes, if you’re being exposed to that kind of light at the wrong time, is it any more beneficial than it is detrimental or problematic for your development?”

His lab has studied both developing mice and human fetal tissue, finding that the timing of light exposure matters. The research could inform new NICU practices and tools for understanding how the nervous system wires itself under unusual conditions.

“Medical practices are rapidly evolving, but our understanding of the fallout isn’t,” he said. “By doing these experiments, what we’re hoping to do is illustrate that we need to be paying more attention to how the nervous system is developing in aberrant sensory conditions.”

Through it all, D’Souza credits his UK mentors, including Dr. Pete Mirabito, Department of Biology; Dr. Ashley Steelman, Department of Chemistry; Dr. Randal Voss and Dr. Douglas Andres, College of Medicine. That foundation, he admits, was his bright start. The combination of research, teaching, and mentoring at the University of Kentucky gave him the resilience to navigate failure and the confidence to pursue science at the highest levels.

When D’Souza first drew the mural in the Biology Learning Center, it was during a lonely summer on campus. “I’ve always wanted to do this thing where we zoom in from the cell, like the nucleus, and then we get up to some fantastical idea of what humanity is,” he said. It was his way of tying together the intricacies of biology with the broader questions of life.

But the mural also carried a message for students who would see it in passing. “Because a cell is doing that every second of your life,” he said. “So you definitely got this, okay? That should be the motivation to keep you going.”